introduced who would control transfers, postings, and promotions in the Air Force and Navy?

By Irum Saleem

“The proposed 27th Constitutional Amendment, which would overhaul Article 243 and recast Pakistan’s military command hierarchy, is the most ambitious restructuring effort in decades and perhaps the most contentious as it collides with entrenched institutional cultures and the fragile equilibrium between civilian and military power,” writes Baqir Sajjad Syed in Dawn.

Its implementation may prove far more difficult than its drafters imagine. The plan collides with entrenched institutional cultures, long-standing inter-service rivalries, and the delicate balance between civilian oversight and military autonomy that has, at least in theory, defined Pakistan’s power structure since 1973.

"Even in the United States, the chairman of the joint chiefs does not wield absolute powers”#Afghanistan#FarrhanaBhatt#PakistanArmy#ARMYhttps://t.co/S8x2dIZb2e

— Zulqernain Tahir (@zulqerr) November 9, 2025

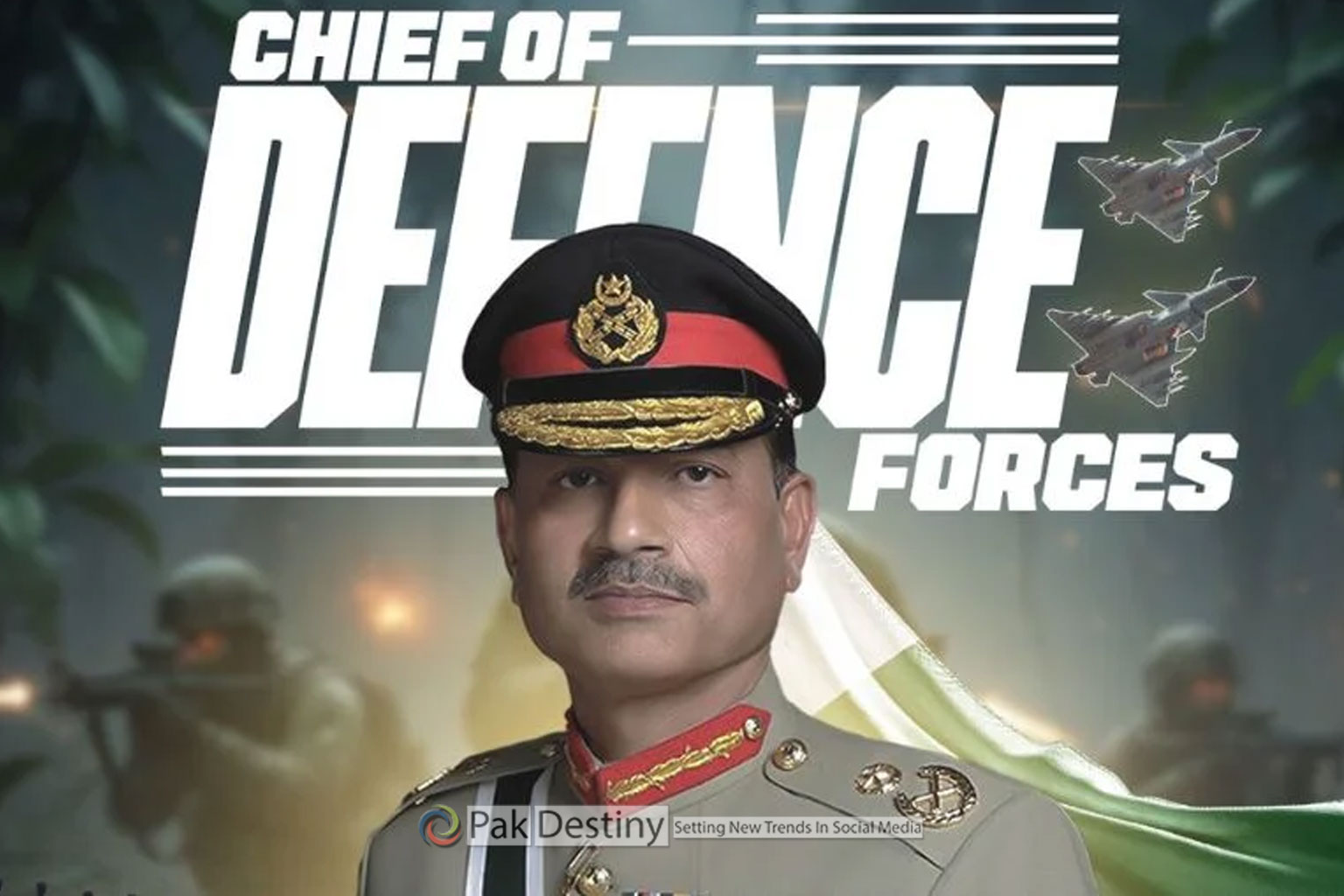

At the heart of the bill lies the deceptively simple premise of modernising defence coordination by creating a Chief of Defence Forces (CDF) and abolishing the office of the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC).

But in practice, the reform would elevate the army chief to a constitutionally enshrined position of supremacy — combining operational command with overarching control of all services.

Article 243 overhaul marks a leap towards military centralisation and consolidation of uniformed supremacy

For over four decades, the CJCSC has served as the symbolic head of the armed services, designed to ensure coordination among the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

In practice, the role remained largely ceremonial, with the army — for over two and a half decades — reluctant to rotate it to other branches.

“The proposed amendment would dissolve the post entirely on Nov 27, 2025, coinciding with the retirement of the current CJCSC, Gen Sahir Shamshad Mirza, and make the chief of army staff concurrently the Chief of Defence Forces — placing all three services under his authority,” he writes.

Former human rights minister and defence academic Dr Shireen Mazari highlights an ambiguity left unaddressed in the bill.

“With the end of the CJCSC position, would the joint chiefs of staff committee also be dissolved?” she asks.

If so, which forum would replace it for coordination among the three services though the CJCSC’s ineffectiveness is well known.

The supporters of the legislation argue that the change will streamline decision-making and enhance unified command.

However, critics see it as institutional capture. “By placing an army officer as the Chief of Defence Forces with authority over the Air Force and Navy, the proposed system invites institutional imbalance and potential disaster,” warns retired Lt Gen Asif Yasin Malik, a former defence secretary.

“This amendment appears tailored to benefit a specific individual rather than to strengthen the defence structure,” he adds.

The criticism cuts to the core of the country’s military culture — the deep-seated rivalries among the Army, Air Force, and Navy, each guarding its operational turf and doctrine.

The Air Force and Navy have long resisted attempts to subordinate their autonomy under land-centric command.

Harmonising these distinct traditions — air power’s rapid, decentralised decision cycles versus the army’s hierarchical chain of command — has historically been the Achilles’ heel of every “joint” reform effort.

A critical question under the new system is who would control transfers, postings, and promotions in the Air Force and Navy.

Would the two service chiefs readily cede that authority? Dr Mazari cautions that if promotions in the Air Force and Navy were to be decided by an army-origin CDF, it “could lead to festering resentments and affect morale in the long run”.

She raises another hypothetical scenario: “What if there is a Marshal of the Air Force or Admiral of the Fleet while the COAS is a four-star general — will they then be under a four-star army officer if the latter is the CDF?” she asks. “Too much has been left to ad hoc and arbitrary decisions.”

Equally consequential is the proposal to create a Commander of the National Strategic Command, a position overseeing the country’s nuclear forces.

Under the amendment, the commander would be appointed by the prime minister on the army chief’s recommendation and must be chosen from within the army.

“That subtle shift moves control of the country’s most sensitive assets away from the collegial National Command Authority (NCA), designed to ensure civilian oversight and inter-service balance, toward a single service” Syed says.

Dr Mazari warns the change could have grave operational implications.

“Effectively, all nuclear weapons and delivery systems will be under the army’s control, including second-strike missiles which normally fall under naval command,” she says.

“This could lead to command-and-control problems and time delays, especially in a war-like situation.”

Her concerns recall a rare moment of institutional dissent — the 2019 National Security Committee meeting after the Balakot strikes — when, according to retired Lt Gen Malik, the then-army chief Gen Qamar Bajwa advised restraint but was reportedly overruled by the air chief and the CJCSC.

“Under the proposed arrangement, would such dissent, and the powerful response it ensured, even be possible?” he asks pointedly.

Perhaps the most controversial innovation lies in the clauses granting life-long constitutional protection to officers elevated to five-star ranks — field marshal, marshal of the air force, or admiral of the fleet.

These officers would “retain rank, privileges and remain in uniform for life”, removable only through impeachment under Article 47 and protected by immunities “similar to those enjoyed by the president” under Article 248, applied mutatis mutandis.

The language is designed to legalise the extraordinary promotion of Gen Asim Munir to field marshal following the India-Pakistan confrontation in May this year.

What looks ceremonial on paper, however, amounts to a permanent legal armour around an unelected officeholder — “a parallel authority insulated from the very rule of law it is sworn to defend”, as one constitutional lawyer puts it, asking not to be named.

Such provisions blur the line between honour and power.

“Even in the United States, the chairman of the joint chiefs does not wield absolute powers,” notes Lt Gen Malik.

“Creating lifetime immunities for military officers upends the very idea of civilian supremacy”. The supporters of the amendment, including government ministers, argue the changes merely formalise existing practices.

Yet the bill remains ambiguous about the tenure of the service chiefs.

Minister of State for Law and Justice Barrister Aqeel Malik told reporters that there was “no need for a fresh notification” on the army chief’s tenure, since existing legal provisions already establish a five-year term under the Army Act as amended by the 26th Constitutional Amendment.

But such reassurances overlook a deeper concern, which is that the proposed amendment will move the defence management from statute to constitutional entrenchment, making future civilian corrections exponentially harder.

Military affairs expert Muhammad Faisal, a doctoral researcher in Sydney, sees the bill as “the first phase” of a broader restructuring.

“There could be more updates coming with changes in the Army Act and NCA Acts to reflect new proposals,” he says.

“This could also lead to the restructuring of strategic forces, currently administered by three services separately, into a unified single command.”

That trajectory — toward centralisation rather than coordination — captures the tension at the heart of Pakistan’s military politics. Every attempt at “jointness” risks hardening into hierarchy because institutional habits and prestige are resistant to reform.

The stakes are profound. The country’s Constitution has endured repeated experiments in balancing military power and civilian authority.

A Chief of Defence Forces position can be created, as many democracies have done, through statutory reform subject to parliamentary review.

But embedding such a role in the Constitution transforms it from an administrative necessity into a permanent political reality, one that cannot easily be undone.

Ultimately, the question is not whether Pakistan needs a modernised defence structure. However, it definitely needs to be updated.

“The question is whether modernisation must come at the cost of institutional equilibrium. History offers a cautionary note that once military power is constitutionalised, it rarely yields ground voluntarily.

Article 243 was meant to preserve civilian command over the armed forces. The 27th Amendment risks rewriting it into a charter of military supremacy,” Baqir Sajjad Syed says.