By Irum Saleem

“No news is good news, and excessive news is a recipe for desensitized teenagers Information overload and hyperawareness are doing more harm than good to Gen Z’s mental health,” says Zunaira Badar Jilali in Dawn.

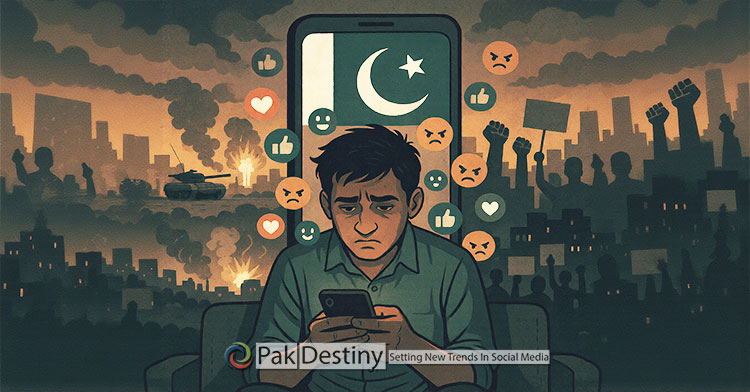

War for breakfast, bombings for lunch, and political unrest for dinner, with a serving of hate crimes and gender-based violence to have with your evening tea. Are human beings actually programmed to process catastrophic information at such an alarming rate?

The advent of digital journalism has eliminated temporal restrictions on receiving news; no longer do you have to wait patiently for the next day’s paper. Or receive a messenger at your doorstep narrating how half your state was annexed while you had the most ordinary day of all time. Our generation has never experienced that — we’ve only known how to scroll for hours, anywhere and anytime, trying to process as much global news as we can at once, since everybody’s in a race to make sure they’re more aware than anybody else in the room.

Psychotherapist Shafa Rashid from Synapse, a Karachi-based neuroscience institute, told Dawn Images, “The cumulative emotional and sensory dysregulation resulting from constant exposure to distressing and tragic news at such a tender age, especially when these anxieties are not adequately addressed by their surrounding environment, but enhanced instead” complicates how people process these events. “This dysregulation and heightened sensitivity of their nervous system is what many teenagers unfortunately carry with them into their twenties,” she added.

“The pressure to have the right opinion” and constantly thinking about how to say the right thing, whether to say anything at all or whether you’ll be cancelled or embarrassed for saying one thing or the other is one of several reasons that create a high stress environment for young people.

“Today, awareness has transformed into hyperawareness as minute-by-minute updates on everything from the US electoral campaign to a local influencer’s dog’s digestive issues are a single tap away. While this easy access to news helps us stay up to date on the atrocities being committed around the world, making it easier to raise our voices, recognise political propaganda and hold the right people accountable, it is also an immense burden on our sensory systems and causes burnout,” Ms Zunaira says.

The issue lies not with the availability of news but with its endless nature. From the Palestinian genocide to the one in Congo, the much delayed controversial Pakistani election, the regime overthrow in Bangladesh, the PTSD triggering return of Donald Trump in the White House, the Pakistan-India war or the Iran-Israel conflict— the doomscrolling is never-ending, precisely because the doom around us is never-ending.

Clinical psychologist Afrah Arshad, founder of Teen Therapy Wellness, told Images that frequent exposure to tragic information can lead the brain to go into emotional overload, initiate a defence mechanism and lead to emotional numbness and detachment. Many teenagers have shared similar experiences of feeling “triggered” and “overwhelmed”.

A sensory overload

Romman Adil, a 19-year-old writer who has penned heartfelt poems for the Palestinian resistance, said that at one point, “seeing numerous reels and posts took a toll on me, and there have been occasions where I have cried and felt hurt for them”. People on internet platforms such as Reddit have shared similar sentiments of emotional arousal.

A forum on Reddit dedicated to Pakistani teens, TeenPakistani, saw similar reactions during the Indo-Pak conflict.

However, this fatigue isn’t exclusive to any one nationality; people across the world share these sentiments.

This doesn’t mean that we have been sentenced to some form of intense torture, but it does hamper our ability to process future atrocities. Especially when we witness graphic media of bloodshed, bombings, burnt bodies, and amputated children over a casual cup of coffee, and study for A-level exams while listening to news of missile attacks destroying geography-defying structures like the Lahore Port, living quasi-dystopian lives.

She further says Rahim, an 18-year-old from Lahore, shared what made him post less frequently, “It’s been going on for so long, I feel like a few story reposts don’t make a difference anyway. When I would post constantly, my Instagram got overloaded with pictures of beheaded babies and people burning alive. Then my exams started, I would open the app after a long day to unwind, and couldn’t bear to look at it. It only made me feel depressed — I know it’s selfish, but it’s what I felt.”

Many teenagers, including Rahim, also feel that the waning of boycott movements around the world is a manifestation of that same hopelessness.

Several 14 to 15 year olds I spoke to related to this feeling.

“Deep down, I do feel the need to notice such matters like Gaza. I do feel bad, but I don’t engage with social media content about it frequently,” said Fariha from Karachi.

“While both mental healthcare professionals, Arshad and Rashid, spoke up about the desensitisation, dissociation, and emotional blunting that they’ve observed in their teenage clientele, they repeatedly emphasised the involuntary nature of it. “It does not mean a person has started lacking empathy. They do care, but their brain shuts down the intensity of their emotional reactions as a defence mechanism,” said Arshad.

Another coping mechanism that is extremely common among teenagers is humour. The meme war during the India-Pakistan conflict — the one in which one side indulged in humour and the other got offended and spewed curse words — is a prime example of how Gen Z will laugh and joke their way through anything. Statements like “the world’s ending anyway, so why should I care?” stem from a sense of powerlessness and self-preservation.

If you poke fun at your own mental health or appearance, or the other dozen crises you’re going through in a tongue-in-cheek manner, nobody will be able to use them against you. Similarly, cracking jokes and laughing off world events is practically a mental blockade to help you dissociate.

Amid the countless tragic videos to come out of Gaza, there have been a few by young Palestinians that make use of humour and sarcasm to get their point across, which is also a commentary on the sad state of affairs that our cognitive processes have boiled down to.

During times when every single day churns out “a major historic event”, headlines flow like water, and a single search takes you down a rabbit hole where you now know the name of Benjamin Netanyahu’s grandfather’s third cousin’s sister-in-law’s cat? Not only does it dampen your spirits, but over time, regular doomscrolling can cause anxiety and desensitisation.

In an article published by Harvard Health Publishing, Dr Aditi Nerurkar, a lecturer in the Division of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, says that doomscrolling can give us “popcorn brain,” which happens when we spend too much time online. “It’s the real, biological phenomenon of feeling your brain is popping because you’re being overstimulated online.”

Such instances of information overload are common during political happenings. In the wake of the 2016 US presidential election, psychologist Dr Steven Stosny coined the term “headline stress disorder”, defined as a “high emotional response to endless reports from the news media, such as feeling anxiety and stress.” Psychotherapist Rashid remarked that when lives go on as usual during a major event such as the Indo-Pak conflict of May 2025, “it creates a disconnect from the gravity of the horrible things happening around us”.

According to Arshad, the clinical psychologist, many teens have described feeling “helplessness, emotional numbness and powerlessness”. They’ve told her that after witnessing years of terrorist attacks and threats, bombings, violence, and school shootings are no longer scary but just another headline to them.

Growing up in Karachi, where news of murders and targeted killings were more readily available than water, I have been witness to how years of exposure have desensitised many to have little to no reaction when they hear this news today. Al Hamd Khalid, a 19-year-old from Karachi, described these circumstances as “living in a dystopian world with a bomb aimed at us at all times”.

Cocomelon for adults

A major contributor to headline-induced anxiety and a sense of impending doom is the dynamic nature of information delivery. Traditional newspapers are one-dimensional in the way that they have limited visuals and stimulate minimal senses. When you had had enough of politicians playing the blame game, you could simply fold your newspaper and toss it into the growing pile of papers give to the raddi wala or ragpicker.

On the other hand, digital media is multidimensional with flashy graphics and trending audio — basically, Cocomelon for teenagers, and you can’t get rid of it even when you’ve had enough. No one’s out here tossing away phones, and deleting Instagram only takes you so far before you redownload it as your primary source of news and communication.

But wait, there’s an even more adult version of Cocomelon available in the form of television talk shows where up is down, down is up, everybody’s screaming, and Firdous Ashiq Awaan is slapping members of the National Assembly. While adults condemn kids hooked to Cocomelon or Miss Rachel, they too are addicted, just to a slightly different drug.

Arshad commented on how “emotionally loaded, bite-sized pieces” of information overwhelm the nervous system, leaving little space for empathy or reflection. “Constant stimulation of audio-visual information can lead to a sensory overload, where the nervous system is in a constant state of hyperarousal, and it can lead to anxiety, irritability, restlessness and physical fatigue.”

Emotional stimulation can impact people differently. For Arham, it forced him to become “more aware and responsible”; scrolling through Instagram and coming across videos from Gaza helped him educate himself, and “in truth, the flashy graphics and trending audio led [him] to support Gaza”. Khalid said, “I feel overstimulated, but I also believe it is necessary for me to feel that way”.

“I would like to add a disclaimer — in no way do secondhand stress, anxiety, and fatigue compare to what people who are living these tragedies go through, and teenagers struggling with feelings of overwhelm acknowledge that as well,” she says. PAK DESTINY